John Chambers is remembered as one of the Greatest Generation. Here’s why.

-

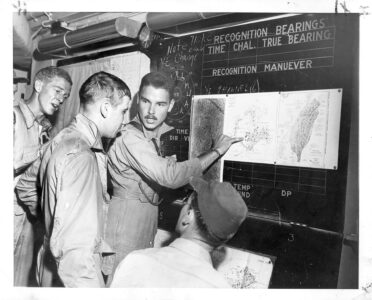

-Submitted photo courtesy of Margaret Chambers

In a briefing, presumably somewhere at sea aboard USS Essex, young John Chambers, foreground, center, listens intently to a briefing, either before or after a mission. Names of others in the photo are unknown. Careful records of all combat missions were kept by the Navy.

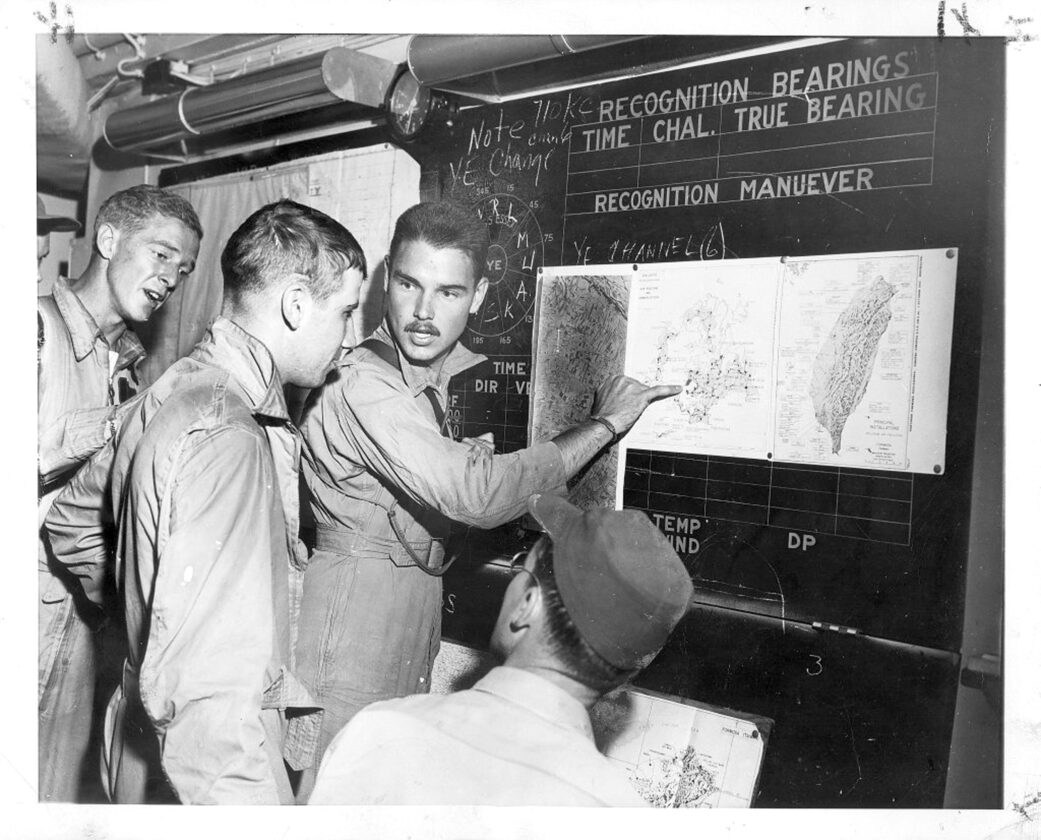

-Submitted photo courtesy of Margaret Chambers

In a briefing, presumably somewhere at sea aboard USS Essex, young John Chambers, foreground, center, listens intently to a briefing, either before or after a mission. Names of others in the photo are unknown. Careful records of all combat missions were kept by the Navy.

Editor’s note: The author gratefully acknowledges assistance for this article from Darlene Dingman, who suggested the topic, and the Chambers family, who generously shared stories and photos of their father’s life.

Journalist Tom Brokaw coined the term Greatest Generation to describe the everyday bravery of men and women who came of age during World War II. Shaped by the Great Depression, they put their lives on hold to save the world from the tyranny of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.

Most of those who did the hard work of war — at the front and at home — were quiet, modest folks who, if they talked about their service at all, would only say they’d done their part. Nothing more.

John Chambers of Webster City was such a man.

Chambers would have blushed at the idea of being a hero, yet there’s no other word to describe his career in naval aviation. Like most service men and women, he was inspired by the courage and comradery of his mates.

In the end, they did it for their country and each other.

The man

John Barry Chambers was born in Webster City October 9, 1918. On November 9, 1943, he married Alice Kennedy. They raised a family of eight in their home at 308 Elm Street, 100 feet from the Webster City Municipal Swimming Pool.

Maureen Seamonds, one of their daughters, recalled, “Our whole family swam every day. Lots of nights we’d still be in our swimming suits eating supper, then go back to the pool again. Some of us were lifeguards. It was the center of life every summer.”

When not swimming, Chambers was delivering mail. He was a letter carrier in Webster City after his discharge from the Navy, until retiring in 1968. He was a life-long Catholic, attending Mass twice each weekend, and daily after retirement.

Alice cooked lunches at St. Thomas Aquinas School for six years before dying from cancer at the comparatively young age of 54. John worked a second job as a janitor at the school. Seamonds simply said, “He never got over Mom’s death.”

Chambers enlisted in the U.S. Navy November 21, 1941, serving until discharged June 1, 1946. He died August 12, 1993.

The mission

The Battle of Leyte (lay-tee) Gulf, largest naval battle of WW II, ran from October 23 to 26, 1944. Aircraft from USS Essex, including one piloted by Chambers, played a pivotal role in the battle, flying combat missions and protecting landing operations of the U.S. Army.

Despite the decisive victory at Leyte, more work was required to rout the entrenched Japanese forces occupying the island and provide a protected landing for the U.S. army.

The little-remembered Battle of Ormoc Bay, in November 1944, was a follow-up action to the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Leyte itself was a strategic point on the sea lanes between Japan, Borneo and Sumatra, Japan’s two major sources of oil. The Japanese built an air field, naval base and fortified gun mounts on Leyte, defending it with a permanent garrison of 20,000 soldiers.

Japan ran convoys between Borneo, Sumatra and Japan, carrying oil to the home islands. The allies had to disrupt this flow of oil and destroy the facilities on Leyte before they could attack the home islands of Japan.

When the battle ended, Japan had lost one of its largest aircraft carriers, three smaller carriers, three battleships, 10 cruisers, 11 destroyers, a submarine and more than 400 planes. Nearly all its experienced pilots were killed, causing it to turn to Kamikaze tactics, in which young, inexperienced pilots sacrificed themselves and aircraft in suicide missions. It also lost 23,000 sailors and soldiers, which was a devastating defeat.

The ship

In the Pacific theatre of WW II, the aircraft carrier replaced the battleship in overall importance. This was compellingly demonstrated with the Japanese use of carriers at Pearl Harbor.

On July 31, 1942, USS Essex, first of a fleet of 24 similar carriers, was launched at Newport News, Virginia. After expedited sea trials, she entered service December 31, 1942.

Steaming across the Pacific in May 1944, Essex carried 120 aircraft, including 70 Helldiver dive bombers, 16 Hellcat fighters, and 36 Avengers. This foretold Essex’s main mission: attack and destroy the Japanese fleet.

Chambers was one of approximately 100 airmen in Carrier Air Group 15, led by the Navy’s ace of aces, David McCampbell. It would soon earn the nickname “Fabled 15” due to its brilliant performance against Japanese ships and planes.

Essex cruised at 33 knots, fast enough to launch and recover aircraft that had crashed into the sea. She carried 2,600 officers and enlisted men.

Essex won 13 battle stars and the Presidential Unit Citation for her WW II service. She served with distinction in the Korean War, took part in many humanitarian operations, and was finally decommissioned in 1969. To get a first-hand impression of what Essex must have been like, you can visit sister ship, USS Intrepid, on display in New York City.

The plane

Chambers completed boot camp at Great Lakes Naval Station near Chicago. Showing an aptitude for aviation, he was given basic pilot training. Although all pilots had to have uncorrected vision, quick reflexes and sound judgment under stress, those who qualified for carrier duty were a special breed. It takes unerring competence and nerves of steel to find and land a plane on a pitching carrier deck in a dark ocean at night in a storm.

Chambers passed muster.

Only those with the best scores went on to aerial gunnery training at Naval Air Station Miami in Florida. Once there, pilots had to choose either patrol and utility, observation or carrier aircraft duty. Chambers either selected or was directed to carrier duty, the most demanding in naval aviation.

The Navy knew family support was crucial for success in pilot training, so Alice accompanied John to gunnery school in Florida. Maureen “Mo” Seamonds was born there.

Chambers’ son Tom, an orthopedic surgeon in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, tells the story of his dad’s first flight from USS Wolverine, the navy’s pilot training vessel stationed at Great Lakes.

“There were two pilots ahead of him, each making their first flight. Both crashed into Lake Michigan, but dad lifted off successfully.”

Naval aviation came into its own in WW II. The Battle of the Coral Sea, May 5 to 8, 1942, revealed several weaknesses in the navy’s planes and torpedoes. Clearly, better planes and armaments were needed to take on the Imperial Japanese fleet and aircraft.

One answer was the Grumman TBF-1 Avenger, the largest, most powerful single-engine plane of WW II. It could carry torpedoes, depth charges or bombs with equal ease. Its top speed of just 259 mph was perfect for its intended purposes.

The Avenger entered service in June 1942 at the Battle of Midway, where it was successful in killing submarines. It had a single, manually aimed Browning machine gun mounted in a turret and another at the rear. Avengers flew with a crew of three: a pilot, bombardier and gunner.

Most early Avenger flights were straight bombing runs against enemy bases, submarines or ships, due to problems with the Navy’s MK-10 and MK-14 torpedoes. It wasn’t until late 1943 that improved contactor mechanisms and firing pins finally gave the U.S. a reliable torpedo. It’s probable that Chambers flew both bombing and torpedo runs in his 37 combat missions.

Tom Chambers remembers his father, who like many who served, talked little about the details, telling him about the day his plane was hit by gunfire, the bullets passing 8 inches under his arm. Those bullets hit his gunner’s leg, which was later amputated.

In another incident, Chambers and several shipmates heard one of their pilots had been shot down and was presumed dead. Someone, remembering the flyer kept a bottle of whiskey in his footlocker, asked that his death be celebrated with a toast by his mates. While they were in the act, the very-much-alive man walked in, extremely unhappy at the misuse of his prized booze.

Chambers was shot down twice: the first time was on June 12, 1944. His plane was hit by anti-aircraft guns at sea and the plane ditched in what the Navy officially calls “a water landing.” The crew survived and were picked up by a destroyer.

A second water landing, at an unknown date and location, was much the same. All crew were safe and rescued by a cruiser of the British Royal Navy, which returned them to the Essex. While at sea, the ship crossed the Equator and, in traditional fashion, the Americans were duly inducted into “the Court of King Neptune,” a ritual for those “crossing the line” the first time.

“The Court of King Neptune” is a hazing ceremony conducted by all the world’s navies. We’re unsure of the precise activities, but the Americans were likely declared unworthy before the king, stripped, thrown into the sea, and rescued by Neptune’s forces. Apparently even in wartime, such traditions were maintained.

The record

From May to November 1944, Fabled 15 fought in 23 major engagements, destroying battleships, carriers, troopships and aircraft. It sank dozens of cargo ships and disabled 12 Japanese bases. It destroyed supply depots, docks and ammunition dumps by the hundreds.

VT-15 sank 174,300 tons of enemy ships, including the Musahi, Japan’s second-largest battleship.

Torpedo 15 earned “revenge” honors when it sank the feared and hated Zuikaku, last surviving carrier from the Pearl Harbor raid.

On November 11, 1944, Chambers, flying an Avenger, helped sink four Japanese destroyers in Ormoc Bay. For his precision flying and bravery that day, he was awarded the Navy Cross.

After Ormoc, VT-15 conducted sea and land raids in the Philippines and against Japanese forces at Formosa (today Taiwan), Luzon, largest, most populous of the Philippines islands; Hainan (a Chinese island in the South China Sea), and Vietnam.

All this success was accomplished in just two years, from VT-15’s commissioning in September 1943 to the end of its service in October 1945.

The reward

On January 11, 1945, Chambers was decorated with the Navy Cross. The official citation reads:

“The President of the United States of America takes pleasure in presenting the Navy Cross to Lieutenant John Barry Chambers, United States Naval Reserve, for extraordinary heroism in operations against the enemy while serving as Pilot of a carrier-based Navy Torpedo Plane in Torpedo Squadron 15 (VT-15), attached to USS ESSEX (CV-9), during action against enemy Japanese forces in the vicinity of the Philippine Islands, 11 November 1944. Striking against enemy shipping, Lieutenant Chambers braved extremely heavy and accurate hostile anti-aircraft fire to deliver his attack and obtain a torpedo hit on a heavy cruiser, leaving it damaged and in a sinking condition. His courage, expert airmanship and unswerving devotion to duty contributed materially to the success of an important mission and were in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.”

An act of Congress established the Navy Cross February 4, 1919, to recognize extraordinary heroism against an enemy of the United States. Recipients’ actions must “go beyond the usual expectations of bravery in battle,” at great risk to their own safety.

A young Tom Chambers remembers playing Carrier Strike! with a buddy in Webster City sometime in the 1970s. The game, by Milton Bradley, required players to launch a plane from an aircraft carrier and guide it safely back to a landing. It isn’t easy. After multiple tries, Tom asked if his dad wanted to try. Without event or comment, John Chambers brought the small plastic plane safely to a landing on the carrier.

On the first try.